Fortune magazine, January 1935

The profile of Shanghai published by Fortune magazine in 1935 caught the old city at its best and most vibrant. It is particularly noteworthy for its view of the Chinese entrepreneurial class and the significance of the Chinese banks based in the settlements. If there had been no Japanese war and you extrapolate the Shanghai exposed in these pages, what would the city have become in another few decades?

The Shanghai Boom began with the self-styled younger brother of Christ and might have trebled your money from ’27 to ’34. Here, the tallest buildings outside the American continent; the biggest hoard of silver in the world; Russian girls; and the cradle of new China.

A city is dedicated land. The dedication may be to government, to trade, to manufacture, to shipping, to finance. But Shanghai’s land, likewise dedicated, is dedicated to none of these. Shanghai, the fifth city of the earth, the megalopolis of continental Asia, inheritor of ancient Bagdad, of pre-War Constantinople, of nineteenth-century London, of twentieth-century Manhattan – where the world’s empires co-inhabit twelve square miles of muddy land at the mouth of a yellow river – is unique among the cities. Shanghai’s land is dedicated to safety.

It was so dedicated ninety years ago, when a few acres along the flat shore of the Whangpoo were set aside by treaty as a spot where foreigners could live and trade. Coming in there for the first time in 1843, on the edge of a miserable and unimportant Chinese town of perhaps 75,000 souls, you bought one acre of that land, on what is now known as the Bund, for about $500 Mex. (The unit of Chinese currency is the yuan, a silver dollar loosely called Mexican. Since it fluctuates less in terms of Chinese commodities than in terms of gold, it is the only fair measure of Chinese values. Hence the dollars throughout this article are Mexican, unless otherwise indicated. The present value of the Mexican dollar is about thirty-four cents.) You proceeded in the next ten years, with the assistance of your armed sloops and merchantmen, to stand off a number of petty local raids. And you discovered by 1860 that you had a reputation for valor among the Chinese, who began flocking onto your consecrated land whenever an up-country revolt occurred.

Then a visionary native who thought he was the younger brother of Christ marched up from the South, sacked Nanking, sacked hundreds of other towns, and descended upon you with an army that resembled in numbers if not in kind the hordes of Genghis Khan. These were the Taipings, whose butchery has been rated at 20,000,000 souls. Before them they swept another army of native refugees, 10,000 of them the first time, 500,000 the second, hotfooting into your foreign haven with bird cages, bedding, rice pots, and all portable wealth. Pause for a moment to remember it: a flimsy barricade thrown up around the bamboo huts and low, granite administration buildings of your concession; a never-ending stream of Chinese, well-to-do, middle class, and coolies, stumbling into the little fortification, huddling in tents on your recreation ground, peering at the white man as he prepared to defend them with his wonderful rifles; the gunboats in the river the sudden surge of the Taiping attack, and the victory. From that victory of 1860, and the more decisive one of 1862, modern Shanghai was born. A trading post was converted almost overnight into a city of some 300,000 permanent residents. And you could have sold your $200 acre of land on the Bund for $50,000.

Now if this sort of thing had never happened again, the value of that acre would doubtless have increased in a normal way, multiplying five or six times from 1862 to 1929. For there was enough trade here to justify a substantial growth. Shanghai fifty-four miles from the open sea, dominates the entire watershed of the Yangtze, which is 3,200 miles long and harbors 180,000 people. The Occident, in the midst of a vast industrial expansion under Queen Victoria and John D. Rockefeller, spilled over into the Orient to spread the Gospel of the Three Lights – the cigarette, the kerosene lamp, and Christianity. While the Manchu dynasty was playing its last cards in Peking, Shanghai grew fat on tobacco, oil, the muck and truck trade, silk, tea, and opium, and attained manhood to the throb of heavy industry. By 1899 the foreign settlement had become so popular with Chinese and foreigners alike that its area was increased for the fourth time. Thus the industrial revolution on the Yangtze.

But that orderly and relentless growth of trade during the nineteenth century was not destined to be the story of Shanghai. In spite of it you may if you like think of Shanghai as dormant for fifty years after 1862,while its land was merely quadrupling in value. Dormant, that is, compared to what happened suddenly in 1911-12 when the Manchu dynasty collapsed forever and the economic forces of 1862 were again brought to bear upon this city of Aladdin’s lamp. This time there rushed to Shanghai not only refugee Chinese but refugee silver. Hoards of it, rivers of it. The revolution fought under the saintly banner of Dr. Sun Yat-sen was not a bloody affair as Chinese affairs go; but the new republican government in Peking was ineffectual. Hence, there dawned the era of the tuchun, the war lord, the local military leader who degenerated rapidly to the status of a bandit. Each was at the other’s throat; none was able to bring more than fifty or sixty million people under his single sway. Chinese and foreign capital alike fled the luchun to Shanghai, where newer and bigger gunboats guarded the banks and their silver hoards. To reinforce the silver there came a slow but insistent stream of Chinese, all clamoring for land, land that was safe. By 1924 the White Man on the Mud Flat had gathered about him 3,000,000 Chinamen. And by 1927 the land on the Bund was selling for $1,400,000 an acre.

And there it might be selling to this day, were it not for one more great attack that is about to descend on Shanghai from the hinterland; one final climactic impetus to its upside-down prosperity. Dimly at first the city learns of wasp-waisted, boyish Chiang Kai-shek marching up from the deep South at the head of the Kuomintang (Nationalist or People’s Party). He marches through the center of China where there are no railroads and few telegraphs, inspiring a revolution as thorough if not as bloody as that of the Taipings. He is heir to the doctrines of the beloved Sun Yat-sen, who died in 1925 after having involved the Kuomintang with Moscow. No one knows how revolutionary young Chiang intends to be; but ahead of his advance there are strikes, labor uprisings, and the Cities are littered with Communist propaganda. And men and money flee once more to the ample Bund on the shore of the Whangpoo.

Chiang reaches the Yangtze Valley, deploys before Rankowand captures it, British Concession and all. Sipping their drinks at the long Shanghai bars, the foreign taipans for the first time feel a profound alarm. The Kuomintang is a nationalist movement, hence anti-foreign. Having ousted the British from Hankow it might grow powerful enough to oust the fourteen nations from Shanghai. It might. The Shanghai businessmen cable home. In response, British, American, French, Japanese, Dutch, Italian, and Spanish transports and cruisers begin converging on the hot spot of the Far East. The Nationalist forces are advancing down the Yangtze. In March, 1927, they capture the native city of Shanghai; sit for a few weeks contemplating the International Settlement; think better of their ambitions; return upriver; and establish a capital at Nanking.

And then two things begin slowly to happen. First, General Chiang brings a degree of internal peace to a great part of his country. The Chinese war lord either is no more or has made a sort of feudal obeisance to Nanking. For seven years there has been no major civil warfare. Second, the world’s greatest depression begins to strangle the world, and especially the trade of the world. Both of these events, coupled with the greatest flood and famine in the history of the Yangtze, ought to have shriveled the value of that acre on the Bund. But the fact is, your $1,400,000 acre of 1927 is today snapped up for $4,200,000.

But why? At this point the explanations become obscure and only the incredible facts are clear. To be sure, General Chiang is still far from achieving a peaceful sway over 450,000,000 people, and by a kind of momentum Chinese silver and Chinese people still seek safety on the Bund. Moreover, a new vitality has come to the Chinese. Nationalism and Westernization have released new forces that were not present in 1860 or even in 1927. But neither of these explanations can account for the orgy of building, the fantastic piling of wealth upon wealth that came to Shanghai during the depression. It is perhaps simplest to assume that there had at length developed within Shanghai itself a momentum that neither floods nor depression nor peace could stop.

In any case, this is the fact: that if, at any time during the Coolidge prosperity, you had taken your money out of American stocks and transferred it to Shanghai in the f orm of real-estate investments, you would have trebled it in seven years. If you had transferred your entire wealth to Shanghai and followed the advice of certain wealthy taipans there you would he as rich today, or richer than you were then. And let the skeptic beware of his Skepticism. For one man in the world actually did this; and the record of his strategy spreads across the pages of financial history as one of the most remarkable phenomena of what we in America known as the depression.

orm of real-estate investments, you would have trebled it in seven years. If you had transferred your entire wealth to Shanghai and followed the advice of certain wealthy taipans there you would he as rich today, or richer than you were then. And let the skeptic beware of his Skepticism. For one man in the world actually did this; and the record of his strategy spreads across the pages of financial history as one of the most remarkable phenomena of what we in America known as the depression.

Sassoon

A BAGDAD Jew by race, though technically an Englishman by birth, Sir Ellice Victor Sassoon is rooted deep in the economic past. His ancestors grew to power in the opium trade in the nineteenth century, invading every nook and corner of the Far East and becoming much involved in the opium wars that Great Britain waged on China, and out of which grew those very treaties that have made Shanghai a consecrated spot. In the nineteenth century Sir Victor’s great-grandfather, David Sassoon, transferred his headquarters from Bagdad to Bombay, and his eldest son, Albert Abdallah, was honored by Queen Victoria with a baronetcy for his contributions to India’s prosperity. David’s descendants include Sir Victor, the hero of this piece; Sir Philip, England’s Undersecretary of State for Air; Siegfried, the able poet; and the Marchioness of Cholmondeley, friend of the British royal family.

Sir Victor was not interested in society, or in great mansions like that of his cousin Philip outside of London with its peacocks and scented swimming pool. Sir Victor saw himself as the inheritor of a great tradition of international trade and finance, and he set forth to build the Sassoon edifice up to new heights. He ran head on, however, into the post-War British tax collector. There was bitterness and recrimination. Sir Victor sat himself down to contemplate international law. Was there no spot where one could put one’s money to work without paying more than half of one’s earnings to a government? He discovered Hongkong. And he discovered Shanghai.

Sir Victor was not interested in society, or in great mansions like that of his cousin Philip outside of London with its peacocks and scented swimming pool. Sir Victor saw himself as the inheritor of a great tradition of international trade and finance, and he set forth to build the Sassoon edifice up to new heights. He ran head on, however, into the post-War British tax collector. There was bitterness and recrimination. Sir Victor sat himself down to contemplate international law. Was there no spot where one could put one’s money to work without paying more than half of one’s earnings to a government? He discovered Hongkong. And he discovered Shanghai.

As a result, during the late twenties, while many of Sir Victor’s companies were incorporated in the British Crown colony of Hongkong, his cash and his credit were thrown, million by million, into Shanghai. Altogether, he transferred from Bombay to Shanghai about sixty lakhs of taels, which is roughly $85.000,000 Mex. He invested the major portion of this and other money in that same magic land along the Bund.

Now it took a certain amount of courage and foresight to plunge into Shanghai real estate in 1927, after the city’s prolonged boom. It was not unlike stepping in on top of the late great Manhattan bull market. Nevertheless, Sir Victor, who is something of a visionary, and his hard-headed lieutenant, Commander F. R. Davey, laid out an ambitious campaign based on the belief that Shanghai was underbuilt. First they organized the Cathay Land Co. and the Cathay Hotel Co. Then, while Shanghai gaped, they put up the Cathay Hotel. This is one of the most luxurious hostelries in the world, rivaling the best in Manhattan and charging Manhattan prices.

Hitherto, the absolute limit in height on that muddy land had been figured at ten stories. But Sir Victor sank hundreds of Douglas firs into the slime, laid a concrete raft on top of them, and on top of that built a twenty-story pyramidal tower, which now dominates the Bund. Its air-conditioned ballrooms have emptied all the older ballrooms in town. And the comfort of its tower bedrooms has brought wrinkles to the foreheads of the managers of the old Astor House and the Palace Hotel.

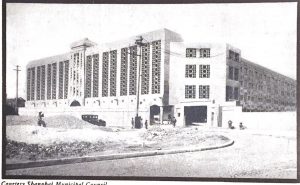

Having taught Shanghai how to build skyscrapers, Sir Victor and the Commander put down the foundations for the Metropole (sixteen stories, 200 rooms, 200 baths). They next proceeded to apartment houses designed to relieve the taipans of the onus of maintaining big mansions heavily staffed. On Kiangse Road they built Hamilton House, a big apartment hotel. They completed Cathay Mansions (eighteen stories), which had been begun by Arnhold & Co. They laid the foundations for Grosvenor House (still abuilding) and threw up rows of Chinese residences, shops, theatres, office buildings. Across Soochow Creek, they erected Embankment House, the biggest building on the China coast (it has a frontage of a quarter of a mile). Spreading out horizontally into the building industry, they bought a hollow-brick factory, financed a firm of interior decorators, acquired Arnhold & Co., an important building-management firm. They bit off big slices of Shanghai’s two investment trusts. Through his private banking business (Sassoon Banking Co. a (E. D. Sassoon & Co.) Sir Victor carried on his usual extensive operations in foreign exchange. And this led him by a devious route to take over the financing and control of the immense Hardoon estate, which has ended in ambitious plans for the reconstructing of Shanghai’s principal shopping street, Nanking Road.

Now Shanghai’s No. 1 realtor, which is a high rank, he lives in the tower of his Cathay Hotel, gives wild, luxurious, and astonishing parties, possesses the only social secretary in the city, strays away to India or England for no more than the few months the British income-tax laws permit him. He is popular in the international set and his immense wealth gives him a special standing. But the crusty diehards of the British colony still look askance at his exuberance and sniff at his ancestry. In England be may hobnob with princes, but in Shanghai, where the Old Guard is almost provincial, there are circles that he cannot enter, partly because he is a Jew, partly because the British deplore his flight from taxation as not quite sporting. A plane crash during the War has left him lame, and sensitive to his lameness. He has never married, and if his tastes in women and horses cause comment he can afford to ignore it. He has left his imprint on Shanghai in the towering bulk of his buildings, he has found a sanctuary for his wealth, and he is great.

Financial center

Had Sir Victor stayed in Bombay during the depression he would not be richer today than he was in 1929. Yet that observation, rebounding much to his credit as a businessman, is relatively superficial. The basic importance of his move arose from its timeliness. And it was timely for two reasons: (1) almost all the Shanghai taipans, with F. J. Raven in the van, had guessed that Shanghai was underbuilt in 1927 and were all set for the orgy in real estate that immediately developed; and (2) a revolution in Shanghai banking destined to change the entire pattern of Chinese finance had been getting under way since the fall of the Manchus in 1912 and now began to flower, injected into this situation, Sir Victor’s sixty lakhs of taels set off an economic Roman candle.

The banking revolution referred to has to do not with the foreign bankers but with the Chinese. China has always been a nation of bankers, If there was no more venal officeholder in the world than the old-style Chinese politician, there was no more capable businessman than the old-style Chinese banker. On the one hand, observers rated him above the Jew in shrewdness and knowledge of money; on the other, his honesty was such that he considered a business default curable only by exile or suicide. He practically gave his life in bond for his customer’s money. But he was not a banker in our Western sense. His operations were generally limited to a personal sphere, he made his money chiefly by feeling his way through the maze of Chinese currencies and money standards, and he seldom dared to lend money to his own government. Though a few Chinese had attempted to imitate Western banking methods for a number or years, the real banking revolution came when Chiang Kai-shek gave evidence that he was the champion, not of Moscow, but of China; and it may be described briefly as a Westernization of those exceedingly astute financial minds, In May, 1928, we have the unprecedented spectacle of native Shanghai banks backing and floating a $10,000,000 bond issue for their own government, almost all of which was sold to the Chinese, And in 1932 we have the even more astounding picture of Finance Minister T. V. Soong balancing China’s budget (a year when no other important budget on earth was balanced) with the cooperation and backing of a group of powerful Chinese financiers whose banks were located in the International Settlement of Shanghai.

Hence the financial plot of Shanghai during the last seven years does not lie with the old established foreign institutions such as the great Hongkong & Shanghai Banking Corp. (British), of which Taipan A. S. Henchman is the dynamic, jittery manager, or with the four other English banks. It does not lie with the four American commercial banks (branches of the National City, the Chase, and the American Express, together with one autonomous institution), or with the three French, the seven Japanese, the Belgian, Russian, Dutch, or Italian houses. These swell the river of money that annually flows in and out of Shanghai, but being based firmly on the old traditions of trade, in which Shanghai flourished in spite of the Chinese, they do not stand out particularly as exponents of the new China. Nor does the plot lie with the thousand-odd Chinese banks in Shanghai (located in the Chinese city as well as in the settlements) that still operate in the “old style,” lending money only to customers whose fathers and grandfathers they have known, though the small Chinese merchant still prefers to deal with them. And it certainly does not lie with the bottom stratum of Chinese banking, the pawnshop, which has banked for the lower classes for centuries. What glitters in the eye today is the new, Westernized Chinese bank – the bank of marble halls, government loans, and statistical departments, of which there are about sixty, all of them in the settlements. And among these, the No. I Westernizer is the Bank of China.

This institution is an out and out commercial bank and must not be confused with the purely governmental Central Bank of China, founded in 1928, forbidden to engage in commercial banking, but issuing notes, controlling currency, and making loans to other banks. The Bank of China is the direct friend and ally of the Chinese businessman, surpassing in its importance to China any of the foreign institutions. It has a capitalization of $25,000,000, assets of $773,000,000, loans of $351,000,000, 44 per cent of which are to the government. Its power is no accident of finance. It has been created by a group of extraordinary Chinese – smooth, Japanese-educated Chang Kia-ngau (see page 115); quick, positive Li Ming; rising, self-educated Pei Tsuyee; and commercial K. P. Chen – who have been leaders in backing their government and financially unifying their people. The Bank of China does a national business in every sense of that word, It has 180 branches, from London and Hongkong, to Chinese towns as small as Shasi (190,500 inhabitants) and as distant as Chengtu (1,800 miles away). Fortified with a modern statistical department, itself a revolution in Chinese technique, it knows more about China than the government, and its annual report is a long, trenchant critique of national affairs. Yet it is not alone. Indeed, it derives much of its power from intimate linkages with such native institutions as the National Commercial Bank, of which amiable, portly Hsu Singloh is General Manager; the Bank of Communications, Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank, the Chekiang Industrial Bank, the Joint Savings Society, the National Industrial Bank of China, and two dozen others, all located in the settlements and all dedicated to a new Chinese financial deal.

These Chinese banks and their polyglot associates are the world’s greatest silver traders. Out of the far-flung international trade upon which Shanghai has been built there has naturally grown a big market in foreign exchange. Every Shanghai commercial house, every bank, must hedge its operations in a monetary chaos which, until T.V. Soong standardized the Chinese silver dollar and eliminated the imaginary tael, was simply too complicated for words.

Yet the Shanghai banker’s role as manipulator of silver has been his cross as well as his cornucopia. First, the presence of the foreign guns in Shanghai has sucked silver from the interior of China, leaving the provinces denuded of specie and deflated. The branches established throughout China by the big central banks act like a sponge to soak up provincial metal, such that a total Shanghai hoard of 50,000,000 ounces in 1922 was doubled by 1925. reached 145,000,000 in 1928, and had rocketed to 393,000,000 by January 1, 1934. Second. while land values in Shanghai were rising, the world depression seriously affected its international trade, which fell from a high of $2,700,000,000 (gross) in 1931 to $570,000,000 in 1932, causing China to export $11,600,000 (net) worth of silver in 1932 in an effort to maintain her balance of trade.

But this was only the beginning. The high price of silver effected by the New Deal in Washington produced deflation in China, raising costs and prices in terms of foreign currencies and hence prolonging the depression by curtailing exports, which remained at $600,000,000 in 1933, and may be lower today. China being normally an importer of silver and an exporter of commodities, the situation looked grave when she exported another $14,200,000 (net) worth of silver in 1933.

But this too was only a beginning. Those same la-di-da theories of international exchange that were put forth by the U.S. Senate (Senator Wheeler said that he wanted to “create purchasing power” in China!) set such a high price for silver in terms of gold that the Shanghai bankers – the foreign ones for the most part, be it said – loaded themselves with profits by selling their silver on foreign markets. What with the shortage of silver in the interior, what with the curtailment of Chinese exports caused by the world depression, what with the speculative urge, there was a “flight of silver” from China; and the country was on the verge of financial collapse a few months ago, with Finance Minister Kung pleading with Mr. Hull for a change in U.S. policy. and Mr. Hull replying in effect that Congress had done it and what could he do? During the first eight months of 1934 silver exports exceeded $170,000,000 worth. Then, on October 17, with $20,000,000 worth scheduled for shipment within the next few days, Finance Minister Kung clamped down the lid and sat on it. A tax combined with an equalization fee now enables banks to ship silver (i. e. China remains on the silver standard) but deprives them of any profit from the operation. Silver exports are limited to moderate balance-of-trade proportions.

In order to combat the drain of silver from the interior to Shanghai, T. V. Soong, China’s dynamo of finance, founded the China Development Finance Corp. in 1934, with the backing of the Shanghai banks, notably the progressive Bank of China. This corporation has a capital of $10,000,000 subscribed to by Chinese taipans, and its function is to arrange for the financing of all sorts of enterprises in the interior and thus stem the influx of capital to Shanghai. Since China is dependent upon foreign capital for her industrial development. “T. V.,” as his U. S. associates call him, has set his cap for Great Britain, for the U. S., for anyone except the Japanese (T.V. is a violent Japanophobe). Progress has been slow because no one dares to invest big sums at any appreciable distance from the Bund. But if and as the power of the Nanking Government becomes consolidated, a rivulet, if not a river, of capital will start to flow back into the land.

The Chinese specie crisis still exists and will continue to exist as long as the precarious balance between gold, silver, and commodities is artificially kept out of line by Washington. But whatever the solution may turn out to be, the point to hold in mind is that the new-style Chinese bankers on the Bund are no longer the mere scapegoats of foreign economic policies. They may still take advantage of the Western cruisers in their river, but Western statesmen can no longer act as if they did not exist. For they do exist – intelligent, powerful, rich, united to the first stable government China has had for twenty years.

The metropolis

So we have come a long way from the mud flats on the Whangpoo; from the bamboo huts, the pre-Civil War rifles. and the howls of the Taipings and the younger brother of Christ. We have come to a city of 3,155,000 souls, doing over one-half the trade of all China; a city second only to Tokyo in the Far East, a city whose real estate market resembles nothing so much as that of Manhattan, with the tallest buildings outside the American continent; the fifth seaport of the world, with 34,000,000,000. Shanghai is, moreover, the chief manufacturing center of China. Here operate eighty-two cotton mills (2,000,000 spindles). 124 cotton-weaving mills. She has ship-building yards, rice-hulling factories, paper mills, egg-product plants, canneries, tobacco, soap, and leather factories – an army of labor that totals 400,000. She has five big engineering firms; she has thirty-five motion-picture producers. She is the insurance center of the entire Orient (see page 115). She has huge utilities, with the biggest waterworks in Asia and one of the biggest steam-electric plants in the world. Her hundreds of banks have deposits of something like $3,000,000,000. She sits upon a throne of silver, the greatest concentrated silver hoard on earth. She sits contemplating the gunboats, the interminable ships, the 50,000 junks that clutter her wharves; there, on her dedicated land, the Mistress of Cathay.

The Shanghailander

To whom, then, the power and the glory of this city? Not yet to its 3,000,000 Chinese, though they have never been so busily self-confident as they are today. And not yet to the 30,000 Japanese, though on their behalf and on behalf of millions of yen worth of textile factories – and on behalf of the Sun of Heaven – the Imperial Army laid waste half the city in 1932: foretaste, perhaps, of ultimate conquest. The glory of this city is still justly claimed by a few thousand families of white men and their predecessors, known as Shanghailanders/ Excluding 25,000 Russian exiles (whom as a group Shanghai does not classify as white men) the number of Shanghailanders, men, women and children, is as follows:

| British | 9,331 |

| American | 3,614 |

| French | 1,776 |

| German | 1,592 |

| German | 1,592 |

| Danish | 385 |

| Italian | 352 |

| Spanish | 274 |

| Dutch | 233 |

| Swiss | 220 |

| Norwegian | 215 |

| Greek | 191 |

| Austrian | 180 |

| Latvian | 154 |

| Czechoslovakian | 139 |

| Swedish | 120 |

| Belgian | 88 |

| Romanian | 86 |

| Estonian | 67 |

| Lithuanian | 60 |

| Hungarian | 59 |

| Finnish | 27 |

| Brazilian | 27 |

| Yugoslavian | 14 |

| Bulgarian | 10 |

| Canadian | 9 |

| Mexican | 7 |

| Argentinean | 4 |

| Peruvian | 3 |

| Cuban | 2 |

| Luxemburger | 2* |

| Spanish | 274 |

| TOTAL | 19,241 |

*Polyglot odds and ends are: Portuguese, 2,113; Indian, 1,842: Tonkinese, 941; Filipino, 387; Polish (largely Russians in disguise), 343; Korean, 151; Armenian. 67; Iraqian, 56: Persian, 55: Syrian, 27: Turkish, 25: Egyptian, 12; Georgian, 4; Dominican, 4; Malay, 2; Afghan, 1; Arab, 1.

Such is the small, snotty, fast-moving club of white people who consider the Mistress of Cathay their own particular preserve. Shanghailander incomes vary from the hundred thousands down to stenographic salaries, but Shanghailanders themselves act as one classless social group. The distinction between taipan and wage earner, old family and upstart, is lost in the glaring fact of their common race.

Just as he is without social classes, the Shanghailander, being neither an alien nor a native, belongs nowhere. He is deracinated. If he has lived long in the Settlement, he will, however, be tinged with a British stain and perfumed with a faint Chinese aroma, the pungency of which will depend upon his personal sympathy with the Chinese. He often despises the Chinese because it is the tradition to despise them. He bars from his upper circle anyone who sleeps with a Chinese woman, though you may have an affair with another Shanghailander’s wife if you like. Conspicuously, he has come to Shanghai to get rich, and specifically to get rich through trade. And he lives in a state of some excitement. His chronic nervousness is not unlike that of wartime and is due partly to his deracination, partly to his knowledge that out of the hinterland whence his prosperity has come, may come also his destruction.

Hollywood has traduced the Shanghailander’s character with tales of unparalleled sin and glamour. And for once Holly-wood’s estimate is not far from the truth. There are plenty of quiet conservatives in Shanghai, but they are not typical and they certainly constitute a smaller percentage of the resident population than in the average metropolis. The Shanghailander drinks too much (his definition of a drunkard pivots around the presence or absence of a drink at breakfast). He is generically loose in his sexual morals. He is apt to be a sports-man-golf, tennis, cricket, bowling, paper chasing, horse racing, and dog racing. And he will gamble on anything under the sun, from the New York Stock Exchange to Manchu ponies and the great $5,000,000 Chinese national lottery.

Enter this world. You arise well after the sun, perhaps in one of Sir Victor Sassoon’s new apartment houses. If you are a big taipan your apartment is an affair of two dozen rooms for which you pay the Sassoon interests $1,000 a month. Instead of the twenty retainers that you used to keep when you lived in a house you have now about nine-a Number One boy, the axis of your household, who may well bring you a cup of tea before you arise; a Number Two boy; two Chinese cooks (male); a house coolie; an amah for your wife; a wash and sew-sew amah; a chauffeur; and a foreign governess. In this Rome of the China coast no one does as the Romans do-since there are no Romans-and hence your breakfast will be strictly national; corn flakes, eggs, and coffee for the American; tea, jam, fish, meat, etc., for the Englishman; chicory and croissant for the Frenchman, and so along. At breakfast you probably read the North-China Daily News, though you have half a dozen papers in English and other languages to choose from. The only American paper is the Shanghai Evening post & Mercury, which brings you Dorothy Dix, crossword puzzles, Ripley’s Believe It or Not, and boiler plate from half a dozen syndicates.

Redolent with the fumes of your favorite tobacco (for you can buy practically any brand in the world), you descend to your waiting limousine and Chinese chauffeur. Its make will follow your nationality, though Buicks predominate among the well-to-do. In the cushions of its tonneau you are now driven a mile or so through the most harrowing streets in the world. Here are the automobiles of your fellow taipans. Here are army trucks, trolley cars on rails, streetcars without rails, on rails, streetcars without rails, man-drawn carts, rattle-brained pedestrians, and bearded Indian police (Sikhs) for whom the new traffic lights are delightful toys. Through it all dart the unpredictable rickshas, like water spiders on the surface of a pool. On every hand you encounter the gaudy cacophonic mixture of the East and the West – the brilliant Chinese banners hung out over the sidewalks announcing bargains and sales contrast harshly with the sign atop the Post Office: POSTAL SAVINGS, and below this, AIR MAIL: TRAVEL BY AIR: C.N.A.C. If you should for any reason debouch at the intersection of Tibet Road with the Avenue Edward VII (where the French and International concessions meet), you would probably get stuck amid a howling of horns and a swearing at the Annamite policeman high up in a pillbox in the middle of the square operating a traffic light. All of which contributes remotely to the tension of your life.

Arriving at your office, which is entirely Westernized, you say good morning to a secretary who, if not American or British, is very possibly Portuguese. If American or British, she is a Shanghailander like yourself – all Shanghailanders are of one single and unique upper class. For a middle class, Shanghai has no income group, but a nationality – and the nationality is Portuguese They originally came to Shanghai in the nineteenth century from the Portuguese colony of Macao. They have since become a race apart, with their own clubs and entertainments and nothing but a business contact with the other nationalities. They are Shanghai’s bookkeepers, clerks, typists, cashiers, and secretaries, paid less than another white man but more than a Chinese – acute, painstaking, inexpensive.

Passing into your private office, you find the cables from home laid out on your desk, elegantly decoded, and containing instructions that you will follow minutely. However, in a brokerage office like that of Swan, Culbertson & Fritz (correspondents of Hay-den, Stone) or S. E. Levy & Co. (White, Weld correspondents), you will be more interested in the news flashes and silver quotations. In a big trading house, like that of Jardine, Matheson, you lumber into action as your predecessors have lumbered for a hundred years, selling cotton, whiskey, battleships, airplanes, toilet seats-the entire what-have-you of staid British commerce. At Butterfield & Swire, another British old-timer, your attention will be taken up chiefly with sugar and shipping. You will find the British-American Tobacco Co. a hive of agents, factory representatives, buyers, and inquiring growers. Or you may sell silk, tea, and piece goods with Gibb, Livingston & Co., Lloyd’s representative in Shanghai; or, at the dingy old offices of the Standard-Vacuum Oil Co. (Socony-Vacuum and Standard Oil of New Jersey) plunge into a tangle of marketing agreements which you have made with Shell’s Asiatic Petroleum Co. for your mutual defense against the aggressive policy of the native concern, Kwang Wha Petroleum Co., Ltd.

At noon you make your way to a club for a leisurely lunch and two cocktails. Most exclusive is the great, gloomy Shanghai Club (British, though other nationalities are elected), whose furniture is heavy and sedate. At one end of the prodigious bar (Noel Coward said, laying his cheek on it, that he could see the curvature of the earth) you will probably find Mr. Arthur W. Burkill holding forth on the economics of rubber, in which speculative Shanghailanders have lost millions. Your lunch is British. After eating it you will let yourself down for a doze into one of the big leather thrones in the library on the second floor. Per contrast, the red-brick American Club, which also elects other nationalities, is bright with American maple and Colonial furniture, its lobby faintly reminiscent of a well-decorated hospital. It is full of eager, smiling men who take you by the hand whether they have met you or not. And its bar is packed. There are any number of other clubs – the Shanghai Bowling Club (limited to fifteen members), the Race Club, the Husi Country Club (founded to promote relations between foreign and native taipans), the Yacht Club, the Cercle Sportif Francais.

You return to your office. But at four-thirty you knock off again for a game of golf at the Shanghai Golf Club or the Hungjao Golf Club, both resembling the Westchester County variety except for the attendants in white nightgowns.

Meanwhile your wife has had a thinner day. She has plenty of servants to run the house but a dearth of intellectual amusements – month-old books and magazines, a woman’s club, a dramatic club, and, if she is lucky, tea with a polished young man from a consulate. All day long she has been looking forward to dinner, and as a result of her prearranging, Shanghai dinners are rigid and pompous, seated with painful precision. Conversation is objective, Continental. suave. Or, in a faster group, it will be racy. Correct wines accompany each course, often chosen with great taste, served by white-gowned, white-gloved attendants. The custom of dressing servants in the colors of the master’s firm is on the wane even among the correct English.

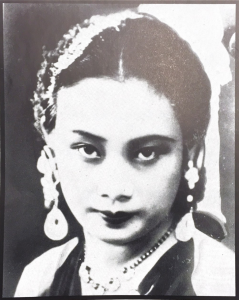

Time was when Chinese and foreign taipans came together in the evening on stiff functional occasions that nobody enjoyed. But recently the social barrier between the races has been breaking down. Pioneers in this movement have been Mr. and Mrs. Chester Fritz (Swan, Culbertson, & Fritz, American brokers). Mrs. Fritz, a striking Hungarian Jewess whose brilliant clothes reflect her sympathy with the Chinese, holds an international salon where distinguished persons of all races and creeds forgather to discuss everything from the markets to the arts. For England, Mrs. G. L. Wilson does similar honors, while Dr. Anne Walter Fearn, ultraconservative American widow, entertains internationally in a more formal way. The new Chinese financiers, politicians, and artists are prominent at these gatherings, together with their wives and daughters.

Time was also when Chinese wives and daughters did not make their appearance in the fashionable night clubs and ballrooms of the foreign rich. When Suzanne Tsang, daughter of the present Commissioner of Reconstruction, Chang Ching-kiang, appeared with a partner at the Carlton Club in 1923, respectable Chinese families were scandalized. But young taipans such as John Keswick (Jardine, Matheson) have taken to inviting young Chinese men and women to their elaborate mansions. The Chinese girls, corresponding to our debutantes, came shyly at first, like pretty wax babies, carrying gold and enamel French compacts in their hands, symbols of a new day. Now they circulate around the town quite freely, smoke, drink, drive their own automobiles.

So, after a meticulous dinner which may well include a number of distinguished Chinese, after the liqueurs and cigars, you and your party of assorted races will probably go out dancing. You may dance at many of the clubs, but the hotel ballrooms and fashionable cabarets are more popular. The toniest cabaret is the Little Club, stuffed every night with fine silks and boiled shirts. But if you are a broker you must leave the party at some time and get in touch with the second shift down at the office to get the New York Stock Exchange quotations when that market opens at 11 P.M. Then, having made your commitments in New York – and if you are a true Shanghailander they will be heavy – and having bid good night to your guests or to your host, as the case may be, the desire will doubtless come upon you to indulge in Shanghai night life more intensely: that is, to dance and chat with the Russian girls. And in this dalliance you will finally have involved yourself in one of the strangest streams of human history, and certainly one of the most romantic elements of Shanghai.

The Russians

On February 7, 1920, Admiral Kol-chak, head of the Russian White armies in Siberia, was shot at Irkutsk by the Reds. Thereupon the White cause collapsed, and petty Russian aristocracy and bourgeois who had fled the Terror to Siberia began a long hopeless retreat which did not end until they reached Vladivostok in 1922. Thousands of these refugees fled to Harbin, Manchuria. No group was ever worse equipped to make a living or ever chose a worse place to make it in. Having natural talents tor singing and dancing, they founded innumerable night clubs at Harbin, such that that city became known as the world’s premier school of entertainment. But there were only poor Russians there and, seeking a better livelihood, men and girls set forth alone or in little groups along the China coast. Presently the girls awoke to find themselves famous. They were not only beautiful: they were reduced to the necessity of earning a livelihood with their beauty, and there were no other white women of this sort in the East. Their popularity became international, as dancers and singers, as mistresses and whores. And thus, like the Shanghailander in quest of riches, they came at length to Shanghai.

Meanwhile other White Russians had reached Shanghai, some overland, some by water, one group of 8,000 (including two refugee Admirals) having sailed down the China Sea from Vladivostok in twenty-seven vessels. The men got work as guards to wealthy Chinese, or as soldiers; the women filled the cabarets. In 1931 the Japanese influence in Manchuria caused a new wave from Harbin to fall on Shanghai, bringing the total up to 25,000 in 1934 – the second largest foreign group in the city. The imminent sale of the Chinese Eastern Railway this year will doubtless start still another wave, may double the present Russian population, will almost certainly double the tragedy of the crowded colony that sprawls through the alleys and byways of the French Concession.

Nor is it possible for the well-groomed Westerner to grasp the full extent of this tragedy unless he reminds himself that these people are cultured and were once well-to-do. Even today a few of the refugees are rich, for before the World War the Russian investment in China, notably in Manchuria, was second only to that of Great Britain. A few, too, have found employment in Shanghai as engineers and professional men. But these are the exceptions. The great majority, though used to money, have none. Moreover Shanghai scorns them and thrusts them into a social group apart, like the Portuguese. The Communists hunt them down. The Chinese, who have never before seen the degradation of a white man, despise and bully them. And because with their arrival white prestige took a beating from which it has never recovered, the whites resent them.

Yet there they are. They have invaded whole sections of Avenue Joffre and other once-fashionable residential districts, where Russian dress shops and beauty parlors have multiplied in absurd profusion among Russian bread shops, restaurants, delicatessens, and tenements packed in between pretentious stone apartment houses. They are a loyal, home-loving people, frequenting their own clubs, fostering their own customs. All they ask is an opportunity to make an honest living, but there is no such thing for them in Shanghai. They start pathetic little shops (as if there were not enough shops in Shanghai!); become manicurists, barbers, waiters, sometimes even capable secretaries to the oligarchy of the Bund. The foreigners help them to support a Russian school and grudgingly buy little white flowers to endow a Russian hospital. Still half of them are unemployed. They gather at night around their samovars to talk over old times. They marry out of their race when they can. They beg, they steal, they sometimes murder.

Beautiful and educated, thousands of their women have gone forth into life of Shanghai to meet fortunes as varied as the city itself. They are popular with American sailors and marines, many of whom have married them. Some become the mistresses of taipans, or near-taipans, and live for a time in ease. The hostesses at the better night clubs dance and drink with any man that comes along, but do not necessarily go home with him. They get a cut on the champagne he buys, the girl being served from a bottle that really contains cider, and they dance with him at the rate of about three dances for a dollar.

If perchance someone happens in who has just come from Russia, they will gather around him excitedly, ask how it is there and whether there is any chance for them to return. They will go home that night and tell the older ones (who remember Russia) what they have heard. But their trail is all downhill. As it goes down you find other and more exotic nationalities mixing in with the Russians, and the locale shifts to the French Concession, where vice is rampant. Here are the soldiers’ dives. Besides, there is an unusually wide selection of good, old-fashioned whore-houses, with Russians again leading. At these you sign “chits” (notes) which are collected at the end of the month by the house shroff. A few Russian girls filter even lower, to the Chinese whorehouses along the river front, where men pay twenty cents and some of the girls have no noses. Most commit suicide before that depth is reached.

The Chinese City

This Shanghai, the polyglot, the industrial, is an anomaly. It stands out like a stain upon the surface of China. It represents China even less than Manhattan represents the U.S. It is unassimilated and strange. In its hectic streets, once you have become accustomed to their exoticism, you are not conscious of the vast, traditionalized interior that China really is; unless, perchance the cry of the carry-coolies – “Hai-yo, hai-yo” – as they jog through the traffic burdened with great bales of cotton or boxes of silver in transit awakes you from your Western speculations to a consciousness of something vast and formidable that you cannot precisely name.

Only in the evening does China creep in upon the Shanghailander, when, in a spirit of exploration or perhaps inadvertently, he wanders from the edge of his protected land into the Chinese City that rings him round. He must remember that, compared with the population of the hinterland, these are sophisticated city folk. Yet, in the parti-colored maze of Neon lights – for the Chinese, a gaudy noisy people, have adopted this Western invention as their own – China is here too. China comes upon him like an invisible wave in the thick, heavy smell of the native quarter, the symphony of smells that no voyageur has yet been able to describe, compounded of open-air cooking, offal, pissoirs, the fumes of opium, and decaying food – the smells that are China. From a lighted window comes the enharmonic wail of a samisen, which will rasp all night; or from a dark doorway a long, high-pitched argument in voices four or five notes too high for the Western ear. Here, in the blind squalor, the tight packing of bodies that live on a scale lower than anything he has conceived of, the adventurous Shanghailander is suddenly overwhelmed with fear and dismay: a pigmy in the vast.

What will arise out of this? May we conceive of a new China, bourgeois-managed and banker-financed, growing up from these mysterious masses, whose monthly incomes average somewhere in the neighborhood of $30 per family and whose roots go back into a civilization utterly alien to the Shanghai Bund? Or is this another Russia, a land of peasants and proletariat, who, at some psychological point in history, will sweep the middle classes aside in a few bloody days, drive the foreigners from their dedicated land (for that is an allied issue), and dedicate their immense slice of Asia to themselves? There are arguments on both sides. And in between the arguments lie failure, chaos, a return to the tuchun.

Kiangwan

IT IS impossible to look far ahead in a world so little known. We can only grasp the immediate facts, and one of these is so big that it is difficult to grasp. It is the fact of Kiang-wan: the new Shanghai, which the bankers and their government are building five miles down the Whangpoo.

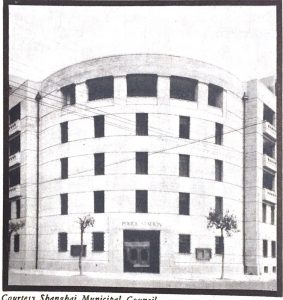

On this hopeful ground work has already begun. Since 1931 the City Planning Commission of Greater Shanghai, headed by German-educated Dr. Shen Yi disciple of rigid German regimentation, has been buying up thousands of mow of farmland at from $300 to $400 per mow (one mow equals a sixth of an acre) and selling it at protected auction for $2,500 per mow.

The big profit is to be used for building the new streets and municipal groups. Buyers scramble for the choice lots and grumble because the native banks get most of them. Sale of land carries with it the stipulation that buildings shall be erected thereon. Boulevards are being laid out, trees planted, bus lines incorporated, police in stalled. The godfathers of the idea are Dayu Doon, a native architect who learned his profession in the U. S., and the American planning experts, Asa Emory Phillips and Carl Ewald Grunsky.

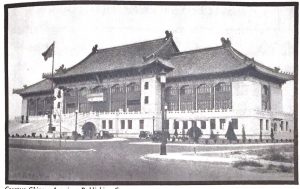

Their composite plan is magnificent, not to say grandiose. A tract of 20,000 acres (more than thirty square miles) has been laid out and divided into rigid zones. The residential district, as yet sparsely built, lies on the flat farmlands to the west. The commercial area extends northward toward the present foreign concessions and will overlap the present native city. At Woo-sung, to the north, a new $20,000,000 harbor will be equipped with an elaborate series of piers and basins. But the wonder of wonders is the Civic Center. Here indeed it seems that East and West have at last met, and the startling architecture of the new City Hall, which is already completed (see page 39), seems to indicate that they have met in wedlock. It is the key to new China. In harmony with it there will rise nine administration buildings, a municipal auditorium, a library, a museum, courthouse-the whole ensemble to be grouped around a twenty-acre plaza and reflected in an artificial pool of water a third of a mile long.

This City Hall, standing out so boldly among empty boulevards and reflected in an imaginary pool of water, is intensely symbolic. It symbolizes, if you like, the year 1776 – and the chief characters that made that year a landmark in U.S. history are being consciously re-enacted 190 miles up the Yangtze River at Nanking, where other startling building projects are in process, Chiang Kai-shek, who marched up from the South in 1926, is playing the role of George Washington before the Chinese people: his name is in every hut and hovel in China, and the picture of his demigod, the late Dr.Sun Yat-sen, in most of them. Former Finance Minister T. V. Soong is Alexander Hamilton. And there are other conscious parallelisms. For these gentlemen, Shanghai banks have floated some $1,000,000,000 in loans. That is to say, the bankers are backing the Chinese George Washington and the social and economic reconstruction that he stands for. They, with their limousines, their foreign houses, their jeweled, educated wives, represent a class-a new middle class, which is as yet a minority but whose nationalistic fervor is spreading out in concentric waves from Nanking and Shanghai. They and their cohorts are intent upon establishing in China the sort of civilization that English, French, German, and American middle classes have brought to fruition in their own lands. They propose to re-enact, to recapitulate in a relatively brief span of years, the entire history of the Industrial Revolution, on the theory that the backward peasants of China can be educated, not merely to read and write with the new 1,000-char-acter “alphabet,” but to work, and make profit, and support a stable government.

The spearhead of their attack is Shanghai. Before Chiang Kaishek marched in, one could have written the story of Shanghai without invoking the Chinese. Today the fact that the Chinese own and operate some 80 per cent of the 3,000 factories in Shanghai must not only be mentioned but emphasized. Their twenty-eight cotton mills are capitalized at $51,000,000; and when Yung Tsung-ching, the native cotton king, cracked in 1934, he disclosed assets of $80,000,000, liabilities of $90,000,000. One towel factory is capitalized at $2,000,000. There are thirty-eight Chinese factories making rubber shoes; thirty-eight for canned goods; sixty for cigarettes; eighty-nine for hats. There are fourteen flour mills; fifteen plants make tooth-brushes. The great Commercial Press, which prints magazines, textbooks, and miscellaneous literature (except newspapers) in every tongue, is capitalized at $3,000,000. The China Mer-chants Steam Navigation Co., now under government control, has total assets of $70,000,000. There are thirty-five motion-picture studios, all native, and of the hundred-odd radio-broad-casting stations in Shanghai, all but half a dozen are Chinese. There are $10,000,000 worth of Chinese public utilities outside of the settlements, and the $5,000,000 Shanghai Inland Waterworks already supplies more than 17,000 Chinese homes.

Add to these industrial enterprises the big Chinese department stores of the concessions, the three largest of which – Wing On, Sincere, and Sun Sun – are clustered together on Nanking Road. In their own way they are just as significant as the new banks, marking a departure from the old-time, small-time Chinese shopkeeper. Sincere is the oldest. It was started by the late Kwok Bew, who went to Australia at fifteen and learned about department stores from Hordern’s big Australian stores, the merchandising of which was based on U. S. ideas. Later, this same Chinese merchant founded the Wing On enterprises – a second department sore, a life-insurance company, a fire and marine insurance company, a bank, a cotton mill, agencies in the Straits and Australia. These two big stores, and the independent Sun Sun, have hotels in their buildings. They have elaborate roof gardens with tables for tea, Chinese theatres, donkeys to ride, distorting mirrors. The natives go shopping here with their entire families and then repair to the roof to enjoy themselves.

As a result of all this Westernization, China’s trade swung into what may prove to be a new cycle in 1933 when she reversed her old position as consumer of manufactured goods and became a producer of them. In that year $157,000,000 worth of manufactured articles were exported to the Straits, to Hongkong. to India, to the Dutch East Indies, to the Philippines, to the U. S. Meanwhile, her import trade has shifted sidewise and now favors the U. S. During 1934 the shift has been accentuated. Were it not for the foreign policy of Washington, which has ruined her foreign credit by boosting silver, China’s purchases in the U. S. would rise still further, for the patriots at Nanking want above all things capital goods. Which, above all things, is what the U. S. wants to sell.

The future

The doughty Shanghailander, driven to his office in the morning through the hectic streets of his adopted city, may look upon these achievements of hers with some pride. For has not he, the foreigner, brought them about? In the past he has. And as a man who has staked out a few millions he cannot but hope for a participation in the future.

But at this point other aspects of the situation intrude themselves to trouble his forebrain. First he is conscious of having come through a world depression. The Manhattan tycoon whose stocks are where they were in 1925, may well deny that the Shanghai taipan, whose real estate is three times as high as it was in 1927, knows even the primer of depression. But the Shanghailander has had his bumps, if for no other reason than that he rides all the financial scenic railways of the world. A city that has lost some 40 per cent of its trade cannot be defined as undepressed. Since Shanghai is built upon trade, quiet will not be restored to the Shanghailander’s forebrain until prosperity is restored to the nations.

If even then. For there are other Shanghai problems that only the future can decide. The new Westernized Chinese middle class that has grown up around the new Westernized Chinese banker troubles the Shanghailander often enough. For he wonders whether it has any roots in China. Its key men, the bankers, are a one-generation phenomenon. They stem from the compradors of the nineteenth century-Chinese financiers who did not act on their own account but as middlemen to negotiate between the foreigners (whose rights they took for granted) and the natives. In Li Ming and Chang Kia-ngau the comprador has become glorified, has taken power into his own hands and now acts for himself. But the government and the economics that he and other Westernized China have set up may be merely synthetic and may be merely synthetic and may never be able to reach down into the masses of China – the farmers, the peasants, the Good Earth.

That danger in itself does not trouble the Shanghailander, for he is accustomed to governmental chaos – has, indeed, risen to power on it. But this time he is impaled upon the horns of a dilemma: if the Nanking Government fails, the Communist movement (which is more widespread in China than in any other nation in the world outside the U.S.S.R.) may succeed, and would doubtless sweep him and his works from their precarious perch along the Bund; whereas should the bankers and Nanking succeed, their intensely nationalistic followers may drive him out just the same. The only difference being that in one case he would probably be killed; in the other he would doubtless be given the opportunity to buy a ticket home.

This dilemma may perhaps explain an anomaly in the Shanghailander’s philosophy: he is never quite decided in his attitude toward the Japanese. The Islanders have invaded the dedicated land with the same treaty rights as other foreigners. They have invested $215,000,000 (gold) in and around Shanghai. Among other things, they operate thirty cotton mills. And what with the Chinese labor (which is even cheaper than their own), and what with their management skill (they are two generations ahead of the Chinese in Westernization), they can undercut China in foreign and domestic markets, with goods made on Chinese soil.

The Shanghailander cannot in justice resent this, since he himself has exploited the Chinese in similar ways for nearly a century. Indeed, if he is a realist, he looks upon Japanese aggression with favor-the only available substitute for the big military stick that Great Britain used to wield. Since England’s Far Eastern policy has softened, and since America’s has never been hard, the cloak of international policeman must fall upon Japan.

But the Japanese are a yellow race, not even admitted by the Shanghailander into his charmed circle. They cannot be trusted. In 1932 they invaded his city, and while Sir Victor Sassoon and a group of friends carelessly watched the bombs and the shellfire from the tower of the Cathay Hotel, they could not tell whether Japan was playing the Shanghailander’s game or playing a lone hand of her own for the conquest of Asia.

If Japan wants Asia there remains one solemn thought that will certainly justify an extra cocktail at lunch. She might enter Peiping tomorrow without causing any serious international repercussions: but when, as, and if she turns her guns on the foreigners in Shanghai…

“Well cheerio, old man. Maskee-pu-yao-chin!”

Appendix I: Men of Shanghai

Cornelius Vander Starr, or C. V. Starr as he styles himself, is Asia’s No. I life insurer; but his insurance career has not been the dull, routine-ridden affair that is so typical of this profession in America. Born in Fort Bragg, California, switched to insurance, joined the Army, caught the wanderlust, got a job with Pacific Mail S. S. Co., arrived in shanghai in 1919 as stenographer with 300 Japanese yen in his pocket. Destiny led him to the office of Frank Jay Raven (see below): and with Mr. Raven he founded American Asiatic Underwriters Federal, Inc. U. S. A. Which prospered mightily.

Cornelius Vander Starr, or C. V. Starr as he styles himself, is Asia’s No. I life insurer; but his insurance career has not been the dull, routine-ridden affair that is so typical of this profession in America. Born in Fort Bragg, California, switched to insurance, joined the Army, caught the wanderlust, got a job with Pacific Mail S. S. Co., arrived in shanghai in 1919 as stenographer with 300 Japanese yen in his pocket. Destiny led him to the office of Frank Jay Raven (see below): and with Mr. Raven he founded American Asiatic Underwriters Federal, Inc. U. S. A. Which prospered mightily.

Fifty year ago in America, life insurance was a fat-profit business, that is, net income per dollar of assets was big. And this because advancing hygiene and medication enabled policyholders to outlive actuarial estimates. One who insured himself at the age of thirty, with a life expectation of sixty, found, upon reaching sixty, that he might expect to live to (say) sixty-five. Consequently, in the reverse bet that every insurance policy is, he lost and the company won.

And so it is today in China. Were the total assets of Mr. Sarr’s companies to be tabulated they would seem midgetlike beside those of Metropolitan Life. But Mr. Starr’s income is fat-perhaps as big today as any U. S. insurance income. This money is earned upon a sociological premise, that the standards of living and hygiene of the Chinese middle classes are improving, with a consequent decline in the death rate. Indeed, since Chinese statistics are all but nonexistent, the success of Mr. Starr’s American Asiatic Underwriters, and of its various subsidiaries, is perhaps the best available proof that the death-rate decline in China is a reality.

C. V. Starr has never bothered to become proficient in Chinese. But his knowledge of China is encyclopedic, and he is famed in the foreign community for his uncanny ability to work with and through the natives. Yet here too his success is basically sociological. Before his gusty arrival in Shanghai, Western insurance men had feared Chinese fraud. Mr. Starr clearheadedly laid it down as an axiom that Chinese fraud was no more to be feared than Western fraud, and proceeded to build up a big native business on minor variations of the practice he had learned in California. Today his insurance agents travel throughout Asia.

Though the Rotary Club has expelled him for speaking his mind, he is Shanghai’s most bullish taipan. But like many of his modern associates, he is bullish in finance rather than in goods. His operations form a vast and intricate web, the outer limits of which no one knows. Typical Shanghailander, he has a passion for speculation in land, owns the Metropolitan Land Co. outright, together with a big chunk of F. J. Raven’s Asia Realty Co. Atypical, he believes in the Chinese, believes that Shanghai, foreign concessions and all, will eventually revert to the Chinese. He follows Chinese housing sharply. He publishes the Shanghai Evening Post & Mercury, the one American daily in Shanghai, together with the Chinese version of it, and a news magazine called East, patterned after U. S. S TIME.

His is a machine-gun mind, tactful at times, but often tough. At the psychological moment he will thrust out his jaw, which, with his glasses, is the most prominent feature of his face. He is forever on the go-Shanghai to New York, New York to London, London to Singapore. He goes with, and in quest of, ideas, talks insurance everywhere, spreads his interests out through Asia, has just purchased the United States Life Insurance Co. in the U. S. (assets, $6,000,000). In his rare periods of quiescence he lives with a maiden aunt on the eighth floor of the North-China Building, 17 the Bund, where Asia Life and American Asiatic are also housed. He belongs to the usual Shanghai clubs, dines out, drinks sherry flips solemnly in corners of hilarious night clubs. He is not really social. And he has never married.

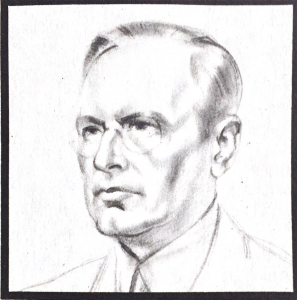

Starr’s good and powerful friend in Shanghai is Frank Jay Raven, and the team of Starr and Raven has surged along with rare interruptions since 1919. Likewise a Californian, Mr. Raven came to Shanghai in 1904, when the foreign settlement was predominantly British. He got a job as engineer from the Shanghai Municipal Council. but was soon lured from his profession by the irresistible economic logic of Shanghai real estate. Starting with assets of $4,000, he had made enough by 1914 to found the Raven Trust Co., on which he proceeded to superimpose what Shanghai calls “the Raven interests” – chiefly the American-Oriental Finance Corp., the American-Oriental Banking Corp., and the Asia Realty Co.-a total of some $70,000,000 in assets. Such was the structure, at least partially built, into which young C. V. Starr stepped in 1919, with the purpose of adding an insurance empire thereto.

Starr’s good and powerful friend in Shanghai is Frank Jay Raven, and the team of Starr and Raven has surged along with rare interruptions since 1919. Likewise a Californian, Mr. Raven came to Shanghai in 1904, when the foreign settlement was predominantly British. He got a job as engineer from the Shanghai Municipal Council. but was soon lured from his profession by the irresistible economic logic of Shanghai real estate. Starting with assets of $4,000, he had made enough by 1914 to found the Raven Trust Co., on which he proceeded to superimpose what Shanghai calls “the Raven interests” – chiefly the American-Oriental Finance Corp., the American-Oriental Banking Corp., and the Asia Realty Co.-a total of some $70,000,000 in assets. Such was the structure, at least partially built, into which young C. V. Starr stepped in 1919, with the purpose of adding an insurance empire thereto.

Usually elected as one of the two American members of the Shanghai Municipal Council, Mr. Raven is a pillar of the American community. Having married Elsie Sites, daughter of a missionary and a fervent dry, no liquor is served at his estate on Hungjao Road. Though extensive, his entertaining is austere; and he is one of the few Shanghailanders whom the Reverend Emory W. Luccock sees regularly in a front pew of the American Community Church on Sunday mornings. Mr. Raven’s principal diversion is tennis, which he plays on his own estate or at the Columbia Country Club or at the French Club. A fervid Rotarian, he too is a bull on Shanghai; but, though President of the Board of the American School, his three daughters are being educated in Heidelberg.

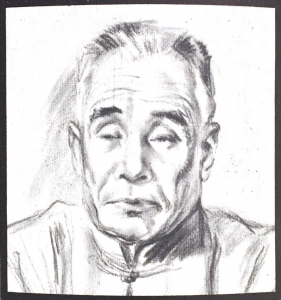

Prototype for Hollywood is Yu Ya-ching, one of the most powerful Chinese in Shanghai. Any Hollywood director would hire him to play the villain in an Asiatic melodrama, for Yu is melodramatic in appearance and thoroughly Asiatic in temperament. He belongs to the old school, which is to say that, born in an obscure Chinese village, he remains at heart a Chinese peasant, secretly antiforeign. You cannot see without a start his reposeful, deep-lined face peering out from the back seat of his big American limousine – the old world condescending to the new, but smoldering still.

Prototype for Hollywood is Yu Ya-ching, one of the most powerful Chinese in Shanghai. Any Hollywood director would hire him to play the villain in an Asiatic melodrama, for Yu is melodramatic in appearance and thoroughly Asiatic in temperament. He belongs to the old school, which is to say that, born in an obscure Chinese village, he remains at heart a Chinese peasant, secretly antiforeign. You cannot see without a start his reposeful, deep-lined face peering out from the back seat of his big American limousine – the old world condescending to the new, but smoldering still.

Yu is a capitalist. But he is not really rich, for he spends all his income in a magnificent Chinese way that Westerners never quite succeed in emulating. His dozen or so concubines are kept in luxury; his entertainments are big shows; and his dependents and satellites are without number. The sources of his income are obscure, and perhaps better left unchronicled; but his official business is with the San Peh Steam Navigation Co., second largest native shipping concern, operating coolie boats to Vladivostok and small steamers to Ningpo, Hankow, and other ports. He is the Director of the Chinese Cotton Goods Exchange. He sits on the Municipal Council. He is Shanghai politician No. I. In fact, he is Big Boss of Shanghai.

As Boss, he is invaluable as a mediator between foreign and Chinese interests. But he is rumored to have more romantic connections. Shanghailanders whisperingly link him with the notorious Three Musketeers of the French Concession-Smallpox (Million-dollar) Wang. Chang Shig-liang, Doo Yu-sen-gentlemen who have to do with opium, sing-song houses, kidnapping, and other Oriental institutions dear to every Hollywood director’s heart. Whether the rumor is true no foreigner really knows. And since Yu is so popular with all nations, no one minds.

A strong contrast, and more representative of the new China. is Chang-ngan, Managing Director and General Manager of the Bank of China, financial ally of the present Nanking Government, educated in Japan. Not for him the concubines and the glamour of the old world. A sharp, dry, practical banker, opportunistic, dressed in Western clothes, he has helped build the deposits of the Bank of China up to $540,000,000. the loans to $351,000,000. And it is peculiarly in those loans that his significance is to be found.

A strong contrast, and more representative of the new China. is Chang-ngan, Managing Director and General Manager of the Bank of China, financial ally of the present Nanking Government, educated in Japan. Not for him the concubines and the glamour of the old world. A sharp, dry, practical banker, opportunistic, dressed in Western clothes, he has helped build the deposits of the Bank of China up to $540,000,000. the loans to $351,000,000. And it is peculiarly in those loans that his significance is to be found.

Until General Chiang Kai-shek,* financed by Russia, marched into the Chinese quarters of Shanghai at the head of the Kuomintang, few Chinese bankers dared to lend money to their own government. National loans were largely obtained from foreign powers, with customs or post-office receipts as security. But Chiang Kai-ahek turned out not to be a Communist after all, in fact he slew every Communist he could lay his hands on. He then bid for the support of the Chinese bourgeois and the Chinese banker. Goaded by his future brother-in-law, Finance Minister T. V. Soong, frequently reigned and as frequently recalled, the native banks began lending money to Nanking. To the fore in the new, radical policy was Banker Chang Kia-ngau, who saw in Nanking the most stable government that China had had in thirty years, and who rallied a big block of Chinese financiers to the Western notion of putting up money to pay for security. Under Chang’s management, 44 per cent of the loans of the Bank of China (about $155,000,000) are now government loans.

To this astute gentleman and his kind must go much of the credit for the present economic awakening of China. In the best banking tradition, Chang seeks solidity and security. Doubtless he will back the present government so long as it provides these sound bourgeois desiderata; doubtless, also, while intensely nationalistic, he holds himself in readiness to play ball with the Japanese. An example of his methods is the new statistical department of the Bank of China, which has broken through the conventional Chinese abhorrence of statistics and actually knows more about China, politically and economically, than the Nanking Government itself. With knowledge gleaned from this department, he and the great Li Ming, Chairman of the Bank of China, can pull wires intelligently and constructively. Thus Chang has come to be a political power in the larger sense, much in contrast to Boss Yu.

He lives at 650 Avenue Haig, at the boundary of the French Concession, where many of his kind who desire a foreign atmosphere but do not wish to live under a foreign flag maintain lavish residences. Speaking English and Japanese fluently, his wit enlivens few Shanghai parties beyond the calculated affairs at which he and his wife preside in their quiet but cosmopolitan home.

Son of a missionary doctor, born in Peiping, educated (as a mining engineer) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Paul Stanley Hopkins is one of the few taipans of second-generation stock. His first job was with the Standard Oil Co. of New York; through its North China Division he rose swiftly, was put in charge of its Hankow office, became No. 2 at Shanghai, became acting No. 1. When Electric Bond & Share, through its subsidiary, American & Foreign Power, was dickering with the Municipal Council for the Council-owned Shanghai Power Co. it offered Mr. Hopkins the presidency of the latter. To Shanghai’s surprise Hopkins jumped from the head of the greatest American trading company in China to the head of the greatest American (or Chinese) public utility in China, gaining much face thereby. Hardboiled to the point of ruthlessness and too dictatorial to be generally liked, he is nevertheless one of the dominant figures in the local business world and is supposed to be the highest-paid local American executive. Chinese have said that he is the only foreigner they know whose Chinese inflection is almost indistinguishable from that of a native. He has a comprehensive knowledge of the Chinese character; his slow speech masks a quick mind tuned acutely to the Chinese scene. No frequenter of clubs or giver of Shanghai’s ubiquitous parties, his entertaining is done by his Smith-trained wife, who sees that he puts on the show his social position requires, and who comes close to being the social leader of the American community.

Son of a missionary doctor, born in Peiping, educated (as a mining engineer) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Paul Stanley Hopkins is one of the few taipans of second-generation stock. His first job was with the Standard Oil Co. of New York; through its North China Division he rose swiftly, was put in charge of its Hankow office, became No. 2 at Shanghai, became acting No. 1. When Electric Bond & Share, through its subsidiary, American & Foreign Power, was dickering with the Municipal Council for the Council-owned Shanghai Power Co. it offered Mr. Hopkins the presidency of the latter. To Shanghai’s surprise Hopkins jumped from the head of the greatest American trading company in China to the head of the greatest American (or Chinese) public utility in China, gaining much face thereby. Hardboiled to the point of ruthlessness and too dictatorial to be generally liked, he is nevertheless one of the dominant figures in the local business world and is supposed to be the highest-paid local American executive. Chinese have said that he is the only foreigner they know whose Chinese inflection is almost indistinguishable from that of a native. He has a comprehensive knowledge of the Chinese character; his slow speech masks a quick mind tuned acutely to the Chinese scene. No frequenter of clubs or giver of Shanghai’s ubiquitous parties, his entertaining is done by his Smith-trained wife, who sees that he puts on the show his social position requires, and who comes close to being the social leader of the American community.

When Sir Victor Sassoon transferred his sixty lakhs of taels from Bombay to Shanghai, he brought along his first lieutenant, F. R. Davey, who had been head of E. D. Sassoon & Co. in Calcutta. Hard-headed, energetic, reserved, Commander Davey is the picture of an English squire. His career began at sea when he was sixteen. He later qualified as a master mariner and during the War earned the present title by which he likes to be addressed. During an interlude in his seafaring he became a journalist, managing a group of British newspapers for several years. He met Sir Victor in the War, and thereafter was persuaded to take up the study of private banking. At this he is now past master. His realistic hand is also laid upon the various Sassoon land companies, together with the Yangtsze Finance Co. and the International Investment Trust.

When Sir Victor Sassoon transferred his sixty lakhs of taels from Bombay to Shanghai, he brought along his first lieutenant, F. R. Davey, who had been head of E. D. Sassoon & Co. in Calcutta. Hard-headed, energetic, reserved, Commander Davey is the picture of an English squire. His career began at sea when he was sixteen. He later qualified as a master mariner and during the War earned the present title by which he likes to be addressed. During an interlude in his seafaring he became a journalist, managing a group of British newspapers for several years. He met Sir Victor in the War, and thereafter was persuaded to take up the study of private banking. At this he is now past master. His realistic hand is also laid upon the various Sassoon land companies, together with the Yangtsze Finance Co. and the International Investment Trust.